“So there remains a Sabbath rest for the people of God. For the One who has entered His rest has himself also rested from his works, as God did from His” (Hebrews 4:9-10).

All quotations are from John Owen, An Exposition of the Epistle to the Hebrews: Vol. II (Grand Rapids: Baker), Reprinted 1980. For a list of relevant quotations, see HERE.

Update: See Part 2 (The Sabbath in the Covenant of Works) HERE.

John Owen makes a distinction between ‘moral’ and ‘Mosaical’ elements in the fourth commandment:

For whereas some have made no distinction between the Sabbath as moral and as Mosaical, unless it be merely in the change of the day, they have endeavored to introduce the whole practice required on the latter into the Lord’s day (p. 441).

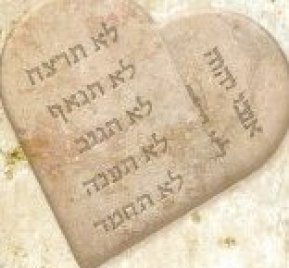

In the above quote, he is making the point that he believes the Christian interpretation of the fourth (sabbath) commandment which requires the entire commandment to be seen as presently binding is wrong. He sees, in the fourth commandment, two distinct elements: the moral and the Mosaical. The moral essence of the command remains binding: “Remember the Sabbath day to keep it holy” (Ex. 20:8). The Mosaical elements, which are ‘explicatory’ of the commandment in the distinct setting in which they are given to Israel are no longer in force: “Six days you shall labor, and do all your work, 10 but the seventh day is a Sabbath to the Lord your God. On it you shall not do any work, you, or your son, or your daughter, your male servant, or your female servant, or your livestock, or the sojourner who is within your gates. 11 For in six days the Lord made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that is in them, and rested on the seventh day. Therefore the Lord blessed the Sabbath day and made it holy” (Ex. 20:9-11).

He explains:

It is by all confessed that the command of the Sabbath, in the renewal of it in the wilderness, was accommodated unto the pedagogical state of the church of the Israelites. There were also such additions made unto it, in the manner of its observance and the sanction of it, as might adapt its observation unto their civil and political estate…So was it to bear a part in that ceremonial instruction which God in all his dealings with them intended. To this end also the manner of the delivery of the whole law and the preservation of its tables in the ark were designed. And divers expressions in the explicatory parts of the decalogue have the same reason and foundation. For there is mention of fathers and children to the third and fourth generation, and of their sins, in the second commandment; of the land given to the people of God, in the fifth; of servants and handmaids, in the tenth. Shall we therefore say that the moral law was not before given unto mankind, because it had a peculiar delivery, for special ends and purposes, unto the Jews? (p. 314).

This view is predicated on the idea that the original Sabbath command was a part of the pre-Fall (Adamic) covenant of works. We will deal with that issue in another post (Update: see HERE). For our present purpose here, I will draw from a contemporary of Owen (and a Westminster Divine): Samuel Bolton. Bolton held a very similar view to the nature of Old Testament Law. He describes the relationship of the moral and Mosaical (which he divides into two parts, ceremonial and judicial; these have also regularly been called ‘ceremonial’ and ‘civil’) in this way:

The ceremonial law was an appendix to the first table of the moral law. It was an ordinance containing precepts of worship for the Jews when they were in their infancy…As for the judicial law, which was an appendix to the second table, it was an ordinance containing precepts concerning the government of the people in things civil…(The True Bounds of Christian Freedom, p. 56).

I have written on Bolton’s interpretation HERE. In that post, I shared a diagram (that I created, poorly I might add) that summarizes Bolton’s view:

Here is the explanation: the great commandment and the second which is ‘like unto it’ (Matthew 22:37-39) are further elaborated in the moral law of the 10 Commandments (or to put it another way, ‘Love God’ and ‘Love your neighbor’ serve as a summary of the moral law). The Moral Law is then applied specifically to Israel by way of the Ceremonial and Civil Laws (which Bolton likens to appendices, something added after the initial laws). The Cleanliness laws are placed in the middle of the appendices, between the Civil and Ceremonial, because they can fall into either or both categories (see the original post linked above for further explanation).

With this in mind, what we find in Owen is this: he believes that appendices to the commandments not only exist after the initial giving of the 10 Commandments, but in the giving of the 10 Commandments themselves. Restating the relevant parts of the quotation above relating to ‘Mosaical’ (Ceremonial/Civil) additions to the Moral Law:

There were also such additions made unto it, in the manner of its observance and the sanction of it, as might adapt its observation unto their civil and political estate…

He lists a few examples of such additions:

…There is mention of fathers and children to the third and fourth generation, and of their sins, in the second commandment; of the land given to the people of God, in the fifth; of servants and handmaids, in the tenth. Shall we therefore say that the moral law was not before given unto mankind, because it had a peculiar delivery, for special ends and purposes, unto the Jews?

While this interpretation might seem strange upon first reading, upon careful review it will be clear that Christians have always made such a distinction (and continue to make such a distinction) in parts of the 10 Commandments. For example, consider the 2nd Commandment (according to the Protestant numbering of the Commandments):

You shall not make for yourself a carved image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. 5 You shall not bow down to them or serve them, for I the Lord your God am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers on the children to the third and the fourth generation of those who hate me, 6 but showing steadfast love to thousands of those who love me and keep my commandments.(Ex. 20:4-6).

The NAS, for instance, makes the point clear by translating ‘carved image’ as an ‘idol.’ Christians understand that the commandment applies to more than carved images. The Westminster Shorter Catechism, for instance, describes the requirements of the second commandment in this way:

Q. 50. What is required in the second commandment?

A. The second commandment requireth the receiving, observing, and keeping pure and entire, all such religious worship and ordinances as God hath appointed in his word.Q. 51. What is forbidden in the second commandment?

A. The second commandment forbiddeth the worshiping of God by images, or any other way not appointed in his word.

We also, at least it seems to me, tend to stray away from the idea of direct, judicial generational curses, realizing that this element of the commandment was tied to the Mosaic administration of the Law.

Next, consider the fifth commandment:

Honor your father and your mother, that your days may be long in the land that the Lord your God is giving you (Ex. 20:12).

The land promise tied to obedience is, at least, radically changed under the New Covenant. It is clear that this promise (based on obedience) was in direct reference to the Promised Land of Canaan.

So then, Owen argues that the the majority of what is known as the fourth commandment is essentially an appendix meant for the children of Israel under the Mosaic Covenant; those elements, he will argue, are fulfilled in Christ, while the moral essence of the commandment, ‘Remember the Sabbath day to keep it holy,’ abides.

We will look at the rest of the argument in detail in future posts. Subjects included will be Owen’s view of the Mosaic Law (with the Sabbath in particular) as a restatement of the Covenant of Works, how Christ’s Law-keeping, death, and resurrection relate to the Sabbath command in relation to the Covenant of Works, and how Christ, fulfilling the Law, begins, in the resurrection, a new creation with a new (Christian) Sabbath – the Lord’s Day.

I had never considered the Law’s inclusion of generational curses to be culturally specific. Perhaps it can be viewed in much the same way as Owen argues for the Sabbath to be viewed- as having specific details for a specific people of time and place, but the principle still applying today, beyond the specifics. That is to say, it is still applicable to say that one who disobeys the Lord is entering into a sort of accursed life, with future consequences, though they may not measure out as promised when the Law was first given and explicated. Or as you say, we stray away from “direct judicial generational curses”, though that leaves room for other sorts.

This seems correct to me, though it begs for comment as to the reconciliation of grace with such an understanding…

Could you specify what you mean by “the reconciliation of grace with such an understanding?” I’d love to comment, I’m just not sure exactly what you mean.You don’t have to write anything lengthy, just a sentence or two.

My personal take on generational curses is that they are essentially fulfilled in Christ, since his atoning work expands forward and backwards and, in a sense, transcends genealogical ties. In other words, if generational curses were carried out severely on all mankind by the letter of the law, then there is no way that I would be a Christian right now, considering that my parents were non-believers (which entails idolatry). That speaks to the graciousness of the new covenant.

As for the principle, I don’t have any qualms with the idea that the actions of one generation affect future generation, but that is not quite the same thing as a judicial curse upon a nation.

‘Curse’ is a difficult word. If you hold to the existence of a covenant of works (which I do), you necessarily believe that all sinners are under a judicial curse and are only justified as they are united to Christ, who bore the curse for them. The issue here has more to do with a *distinct* curse related specifically to the second commandment.

Yes, I see the point you are making about a “distinct curse” judicially related to the second commandment. And yes, I was broadening the word “curse” to perhaps a more proximal level when using it to refer to “actions of one generation affecting future generations”.

The reason this observation begs for comment in regards to grace is because people will wonder why grace absolves one kind of curse (2nd commandment) immediately, while often leaving the other to reek havoc, atleast in this life. A person might say for instance, “why does the grace afforded me by the blood of Christ absolve my idolatrous heritage, but not the nutritional decisions of my forefathers which now impacts my health today?” (This assuming such nutritional decisions were committed in sin, such as gluttony.)

First, in regards to the distinct judicial element, you have passages like 2 Chronicles 7 that promise (in the old covenant) restoration for Israel as a nation should they repent.

Second, using the phrase you used, ‘nutritional decisions,’ you could say that there is a spiritual sense in which the blood of Christ does absolve the ramifications. His people now have the privilege, and indeed must, eat and drink his blood. We now receive spiritual nourishment in Christ through faith.

If you broaden this out from a simple ‘spiritual application,’ I think of Jonathan Edwards statement that the family is meant to be ‘a little church’ and a little forepicture of heaven. And even broader I go back to my statement about the Lord’s Day being a picture of heaven now. I do not see that my own conversion and justification has changed my parents; nor has it eradicated some of the bad things I inherited; but I now have the privilege of being a part of a new family (with my wife and kids) and another new family (the church) in which the culture is entirely different. I have people who will share my burdens and nurse me in my sickness and sin. And besides that I have the promise that Christ stands beside me so that when I am weak is precisely when I am strong. He does not promise that I will escape suffering in this life, but he does promise me a life to come, and a new world where there will “no longer be any curse.”

It’s all going to happen. I have foretastes of it now. But my patience is still lacking; but the Lord is not slow as some count slowness.