My history with the question of the relationship between meaning and application began, years ago, when a friend asked my opinion of this statement:

A particular statement [of Scripture] may have numerous possible personal applications, but it can have only one correct meaning (R.C. Sproul, Knowing Scripture, p. 39).

My initial take was that this seemed correct enough. The Bible can’t say that something is blue and red at the same time and in the same way, right? The Bible would never claim that 2+2=5. But after we discussed this question over the course of time, we were left asking the question of whether this sort of way of looking at the Bible actually turned the student of the Bible into a mathematician. Sure, the Bible cannot say 2+2=5, therefore all we need to do is be good mathematicians. In studying the Bible, we want to make sure that we are getting the correct answer every time.

So, how do we get the correct answer? By understanding the original context of the writing of the text. We must become historically-minded exegetes who can dig down beneath the layers of historical interpretation and discover the original historical context of the text. From there, we must unearth the original reason for the writing of a particular text to a particular people in that original context. From there, we discover the illusive ‘original intent.’

Once we have found that original intent, we follow the basic rule of hermeneutics. Gordon Fee and Douglas Stuart, in How to Read the Bible for All Its Worth, set forth this proposition:

On this one thing, however, there must surely be agreement: A text cannot mean what it never meant. Or to put it in a positive way, the true meaning of the biblical text for us is what God originally intended it to mean when it was first spoken (p. 30).

And bingo! We’ve arrived at the meaning of a text. Now what? Now we can begin to make applications, based on that original meaning, to our present context. This all sounds rather scientific, does it not? And herein lies the problem.

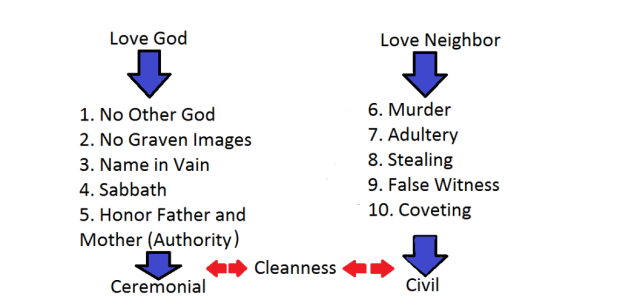

Anyone who has wrestled with the Scriptures understands that the distinction between meaning and application is not so simple. For instance, let’s do some deconstruction on the idea that ‘a text cannot mean what it never meant.’ The idea here is that a text can only ‘mean’ what it could have ‘meant’ for its original audience. John Frame, in his book The Doctrine of the Knowledge of God, uses the example of embezzling to deal with this idea. Does “You shall not steal” mean “You shall not embezzle” or is “You shall not embezzle” an application of “You shall not steal”? Perhaps it was possible for second generation Israelites of the wilderness years to embezzle. If it was, then “You shall not embezzle” could be included in the meaning of the text. ‘A text cannot mean what it never meant,’ but perhaps it could have meant that. But what about this: does “You shall not steal” mean “You shall not illegally download movies on the internet,” or is that simply an application of the commandment? The original human writer couldn’t have meant that. The original audience would never have understood it that way. But it seems logical to say that illegal downloading is a form of stealing and therefore “You shall not steal” does indeed mean “You shall not illegally download movies from the internet.” “You shall not steal” means more than that, but it would seem this is a part of the meaning of the words.

One could think of a thousand examples like this. ‘Coveting’ originally applied to your neighbor’s house, and wife, and donkey. God explains, to the original audience, what he means by adding particular applications of the principle. But what about your neighbor’s BMW? Is ‘not coveting your neighbor’s BMW’ a part of the meaning of the text or simply an application of the text? I am not making the case that all application of Scripture is necessarily included in the meaning, but I want to demonstrate that the distinction between meaning and application is not as simple as some would have us think.

Next, let’s briefly consider the notion of ‘good and necessary consequence.’ The Westminster Confession of Faith (1:6) uses this language, as did many of the Puritans. Here is an example of the idea from John Owen:

Moreover, whatever is so revealed in the Scripture is no less true and divine as to whatever necessarily followeth thereon, than it is unto that which is principally revealed and directly expressed. For how far soever the lines be drawn and extended, from truth nothing can follow and ensue but what is true also; and that in the same kind of truth with that which it is derived and deduced from. For if the principal assertion be a truth of divine revelation, so is also whatever is included therein, and which may be rightly from thence collected…(Works of John Owen, vol 2, p. 379).

Owen, in a discussion on the doctrine of the Trinity, is making the case that the ‘application’ (or, to put it another way, the implications) of Scripture carries the same divine authority as the very ‘words’ of Scripture. Therefore, in the context of our discussion, this means that “You shall not illegally download movies from the internet” carries the same divine authority as “You shall not steal.” If, Owen says, an idea “is included” in “divine revelation” and therefore may be “collected” from it, then it carries the same authority as the very words of Scripture. John Frame recognizes this same principle:

Unless applications are as authoritative as the explicit teachings of Scriptures…then scriptural authority becomes a dead letter (The Doctrine of the Knowledge of God, p. 84).

From here, I want to share a number of helpful quotes that unpack this idea.

Martyn Lloyd-Jones, in the preface to his commentary on Romans 3:20-4:25, makes this statement about preaching:

Moreover, it is vital that we should understand that an epistle such as this is only a summary of what the Apostle Paul preached. He explains that in chapter 1, verses 11-15. He wrote the Epistle because he was not able to visit them in Rome. Had he been with them he would not merely have given them what he says in this Letter, for this is but a synopsis. He would have preached an endless series of sermons as he did daily in the school of Tyrannus (Acts 19:9) and probably have often gone on until midnight (Acts 20:7). The business of the preacher and teacher is to open out and expand what is given here by the Apostle in summary form.

This is quite a statement: ‘The business of the preacher and teacher is to open out and expand.’ That means, if we make sharp distinctions between meaning and application, then the preacher is mainly concerned with application. After all, you can’t really ‘open out’ or ‘expand’ the meaning of a text if the meaning is once and for all settled according to its original context. But, if we take Frame’s perspective, we don’t want to make such a distinction:

The meaning of a text is any use to which it may be legitimately be put. That means that in one sense the meaning of any text is indefinite. We do not know all the uses to which that text may be put in the future, nor can we rigidly define that meaning in one sentence or two (Frame, p. 198).

The applications we are making, if they are an opening outward of the text, that is, if we are (in Owen’s words) ‘deducing’ from Scripture and opening up what is ‘contained therein’ are actually implied in the text. We are merely expounding the meaning. This, again, shows that a clean distinction between meaning and application is hard to make. And it means, for the preacher, that it is quite alright to be ‘application-heavy,’ so long as the application is bringing out the meaning of the text (even if that meaning is latent or implied or is drawn out from necessary inference).

The major objection to this line of thinking is that it opens up the possibility of adding to Scripture. Fee and Stuart’s primary argument for the notion that ‘a text cannot mean what it could never have meant’ is that extending meaning to contemporary applications could lead to the possibility of ascribing words to God that he never said. I don’t doubt that the idea could be abused in that way, but there are answers to such objections:

Implication does not add anything new; it merely rearranges information contained in the premises. It takes what is implicit in the premises and states it explicitly. Thus when we learn logical implications of sentences, we are learning more and more of what those sentences mean. The conclusion represents part of the meaning of the premises.

So in theology, logical deductions set forth the meaning of Scripture. ‘Stealing is wrong; embezzling is stealing; therefore embezzling is wrong.’ That is a kind of ‘moral syllogism,’ common to ethical reasoning. Deriving this conclusion is a kind of ‘application,’ and we have argued that the applications of Scripture are its meaning. If someone says he believes stealing is wrong but he believes embezzlement is permitted, then he has not understood the meaning of the eighth commandment…

When it is used rightly, logical deduction adds nothing to Scripture. It merely sets forth what is there. Thus we need not fear any violation of sola scriptura as long as we use logic responsibly. Logic sets forth the meaning of Scripture (Frame, p. 247).

The clearest biblical illustration that sharp distinctions between meaning and application are problematic is our Lord’s Sabbath-encounter with the pharisees recorded in Matthew 12. Here are verses 1-7 from the ESV:

At that time Jesus went through the grainfields on the Sabbath. His disciples were hungry, and they began to pluck heads of grain and to eat. 2 But when the Pharisees saw it, they said to him, “Look, your disciples are doing what is not lawful to do on the Sabbath.” 3 He said to them, “Have you not read what David did when he was hungry, and those who were with him: 4 how he entered the house of God and ate the bread of the Presence, which it was not lawful for him to eat nor for those who were with him, but only for the priests? 5 Or have you not read in the Law how on the Sabbath the priests in the temple profane the Sabbath and are guiltless? 6 I tell you, something greater than the temple is here. 7 And if you had known what this means, ‘I desire mercy, and not sacrifice,’ you would not have condemned the guiltless. 8 For the Son of Man is lord of the Sabbath.”

The issue of Christ’ s discussion with the pharisees is whether or not it is permissible to pluck and eat heads of grain on the Sabbath. The pharisees say that the disciples are breaking the fourth commandment (Remember the Sabbath…) and Jesus contends that they are not breaking the fourth commandment. Jesus questions the pharisees’ interpretation by asking them whether or not they have read other portions of Scripture: ‘Have you not read…’ Indeed, there is little doubt that the pharisees had read all of the Old Testament Scriptures. Rather, it seems that Jesus’ main point is that they had misunderstood the Scriptures. They knew the words, but they were not able to make proper application of the words. In this case, their misapplication of the words of Scripture would have deprived Christ’s disciples of a Sabbath snack and therefore allowed them to remain hungry. Jesus says that the satisfying of their hunger is more important than extra-biblical laws about labor on the Sabbath.

Notice that this is a battle of applications. Jesus charges the pharisees with misapplying Scripture and he leads them down the interpretive road to true application. But is that all that is going on? The main point I want to make is that Jesus is essentially charging the pharisees with misunderstanding the Bible. In other words, their faulty application of Scripture meant that they had not understood Scripture. They had not only missed the application, they had missed the meaning. If you think that the fourth commandment means you can’t pick an apple and eat it on the Sabbath, then you do not understand the meaning of the fourth commandment. It is as if you have never really read it to begin with.

Charles Spurgeon has a wonderful sermon on this text HERE entitled How to Read the Bible. At one point, he says this:

I think that is in my text, because our Lord says, “Have ye not read?” Then, again, “Have ye not read?” and then he says, “If ye had known what this meaneth”—[that] the meaning is something very spiritual. The text he quoted was, “I will have mercy, and not sacrifice”—a text out of the prophet Hosea. Now, the scribes and Pharisees were all for the letter—the sacrifice, the killing of the bullock, and so on. They overlooked the spiritual meaning of the passage, “I will have mercy, and not sacrifice”—namely, that God prefers that we should care for our fellow-creatures rather than that we should observe any ceremonial of his law, so as to cause hunger or thirst and thereby death, to any of the creatures that his hands have made. They ought to have passed beyond the outward into the spiritual, and all our readings ought to do the same.

By ‘spiritual,’ I do not think he means that there is some ‘higher meaning’ of a text. Rather, he means that you must bring the text out and down – open it up and apply it in a personal way that is consistent with the rest of Scripture. To do this, I am arguing, is to open up the meaning of a text.

We now have a basic sketch of the argument I am making. From here, let me summarize, and then move on to a few implications of the argument.

In summary, sharp distinctions between meaning and application are difficult to make at best. I fear that the making of such distinctions comes out of a desire to seek ‘scientific objectivity’ in interpretation. Such objectivity is impossible. And even if it were possible (and I don’t think it is), it is still undesirable. My argument is that objective detachment in biblical interpretation is impossible and/or undesirable for at least two reasons: 1) Interpretation (even in determining the original context of portions of Scripture) necessarily involves asking questions of the text, and questions cannot be neutral and 2) the best biblical interpretation is also the most applicable and vice versa (the worst is the least applicable). I will pursue those points in the next post with a little help from Neil Postman and Michael Polanyi.